Most of our rooms are not prepared for cold or heat. We are still a long way from the much desired energy efficiency, which will bring us greater thermal comfort and which will allow us to considerably reduce the levels of energy poverty in the country.

In Portugal, people still die of cold, especially in rural areas and among the older population. The figures put forward by the National Institute of Health Ricardo Jorge, in 2019, show that around 400 people die every year in Portugal due to the cold, and exposing a problem that does not seem to have an end in sight, at least in the short term: the energy poverty. So it is called “the inability of families to cover their thermal comfort needs, to adequately heat or cool their homes”, explains Eduardo Moura, Deputy Director of Sustainability at EDP. Allied to this, the cold and humidity, which alone aggravate chronic diseases and other respiratory or cardiovascular complications, exacerbate the effect of excess mortality in winter.

A global problem

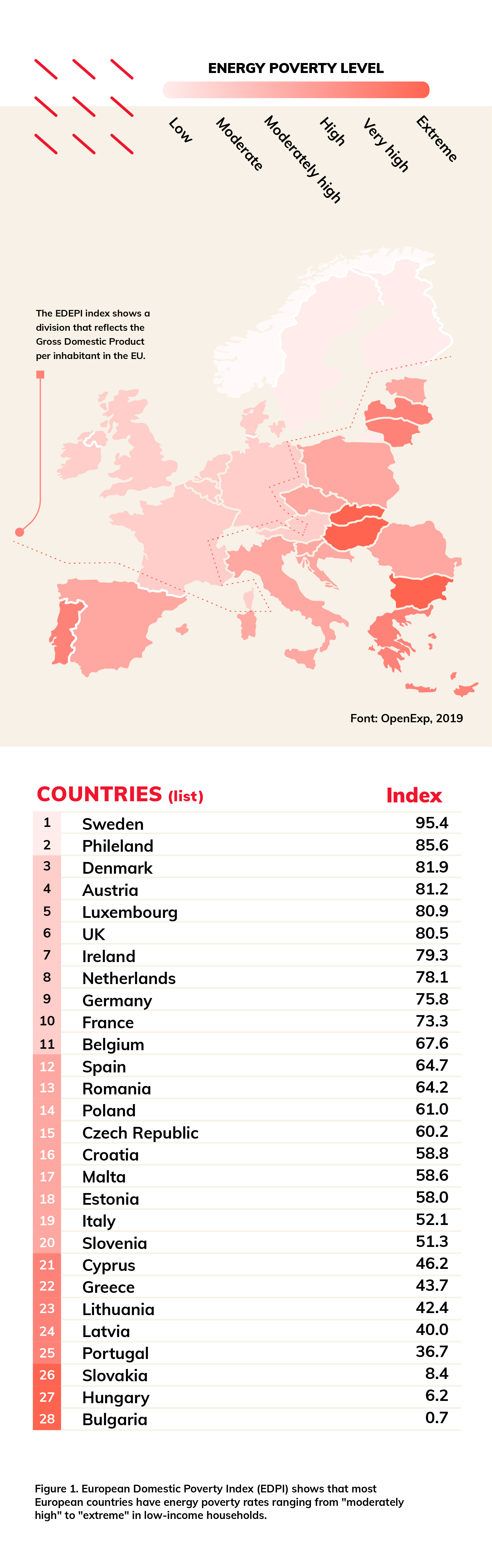

According to the European Union Observatory on Energy Poverty, more than 50 million European households live under energy poverty. This is a problem that the European Union wants to solve.

Analyzing Europe's ranking in terms of energy poverty, it is clear that the countries that traditionally occupy the top of the table in terms of other indicators of wealth, are also those that occupy the top half of this table, as is the case of Sweden, Germany and France.

A very energetically poor Portugal

Although this reality is not exclusively Portuguese, our country is far from looking good at European level: as can be confirmed in the previous table, Portugal shows up at the bottom of it, in 25th place, as one of the countries with the highest level of energy poverty. Published in 2016, in the "Journal of Public Health," based on the statistics between 1980 and 2013, a ranking of winter excess mortality in 30 European countries (which, nonetheless, doesn't refer exclusively to energy poverty as a cause), reveals that Portugal places in 2nd, just behind Malta, counting with an average increase of 28% in deaths occurring between December and March, compared with those that take place in the warmer months. Yes, since heat waves in summer are also associated with an increase in the number of deaths, but in the winter the effect tends to take longer to be felt.

"When we talk about thermal comfort, we talk about a cultural, subjective even, concept: two different people will have different thermal sensitivities. Despite this, the World Health Organization stipulated a standard of thermal comfort, in the temperature ranges between 18ºC and 21ºC in winter, and 19ºC and 23ºC in summer. If the ideal is within these ranges, it is by structural thermal comfort", says Eduardo Moura. This does not happen in the vast majority of the Portuguese housing stock. Why? "According to the study that EDP asked of ISEG, the first conclusion is that 75% of the national building do not have minimum thermal insulation conditions. In other words, in order to ensure such a range of thermal comfort, people have to resort to heating and cooling devices, when this would be unnecessary or greatly reduced if the dwellings had other quality of construction. It all starts there", continues Eduardo Moura.

In addition, in Portugal there is no culture of acclimatizing the house to comfort levels - the most common is to use several layers of clothing first, blankets when you are on the sofa in winter and fans in summer. most of the houses in Portugal do not even have the equipment to air-conditioning the house (and not just one or two specific rooms) and efficiently.

A vicious circle of poverty

As Portugal is not one of the coldest countries in Europe - it is, indeed, far from it - it is now clear why it is colder in our territory than in other countries with much lower temperatures. According to Eurostat data for 2019, 19% of the Portuguese population - more than double the European average - recognizes being in a state of energy poverty and have no financial conditions to warm the house in winter. "Let's say that most economically poor people are also energetically poor, but it has also been concluded that there are people who are not economically poor, but are energetically poor. And there is a moment from which on I will have to invest so much money in energy qualification housing measures, to get out of thermal discomfort, that I became economically poor", explains Eduardo Moura.

“Most economically poor people are also energetically poor, but it has also been concluded that there are people who are not economically poor, but are so energetically”.

Eduardo Moura, Deputy Director of Sustainability at EDP.

How to solve energy poverty

According to Ana Quelhas, Director of Energy Planning, measures to combat energy poverty are divided into three groups: “Consumer protection measures, such as deferred payment contracts and protection against disconnection; measures to support the price or income of families, such as the social tariff or the allocation of subsidies in the cold months; and measures to reduce needs, including energy efficiency ”

This integrated vision, however, is not yet the reality in Portugal, which has "the Social Tariff as the only policy to combat energy poverty," being one of the five EU countries that only has one measure in place. Belgium is the EU country with the highest number of measures, with three measures in each of the three groups (nine in total)). Since this cross-cutting problem is for much of the Portuguese population, the government's intervention is urgent and should not be confined to the social tariff of electricity and gas, with automatic discounts on invoices of economically vulnerable consumers, financed by energy producers. Even more so, since the reduction in the invoice's price in this fringe of the vulnerable population does not solve the fundamental problem, which is in construction. "In the isolation of facades, roofs, doors and the replacement of windows by other efficient ones. Long-term energy-enabling programs are needed for the building, to reduce the number of homes that promote energy poverty. The social tariff is not enough", says Eduardo.

"Social tariff is important in that it is a relief to the family budget, but it is an incomplete instrument in fighting energy poverty since it doesn't tackle the problem at it's root. A more structured way to solve the problem involves investing in the quality of house construction, as well as energy efficiency equipment. These measures reduce the need for air conditioning, causing a price support measure, such as the social tariff, to be lower every year, or even unnecessary", adds Ana Quelhas. That is why the recent initiative of the Portuguese Government, Edifícios mais Sustentáveis, is a positive step, by contemplating a number of benefits and support so that the Portuguese turn their homes more efficient.

"A more structured way to solve the problem involves investing in the quality of construction of houses and in energy efficiency equipment."

Ana Quelhas, Director of Energy Planning.

In search of energy efficiency

If the legal minimum for a new housing is the B- energy class (on a scale of A + to F), it can be said that the minimum level of construction quality at the level of energy efficiency is set in that parameter, and also in the energy comfort standard defined by the WHO. This means that 75% of the Portuguese housing stock is inefficient from an energy point of view, with a C or lower rating.

On the road toward carbon neutrality in 2050, Member States of the European Union will have to double the rate of renovation of buildings by 2030. The goal is that greenhouse gas emissions from buildings will be reduced by 60% in 2030, compared to at 1990 levels. To this end, the European Commission presented the “Renovation Wave”, with the main strategic lines to accelerate the renovation of buildings. In parallel, the Recovery and Resilience Mechanism - a financial instrument created to support Europe's post-Covid economic recovery - also provides support for energy efficiency in the Member States.

In addition, countries are also obliged to monitor their energy poverty situation and introduce specific measures to combat it.