Everyone knows that on Dec. 31 at 11:59 p.m., the telecommunications networks essentially grind to a halt.

There are too many calls wishing a Happy New Year, so people have become used to calling five minutes before or five minutes after midnight. But suppose the same thing happened to the power grid. Would anyone just agree to being left in the dark? When it comes to electricity, the system must remain in operation no matter how high the demand.

In a world with ever growing consumption needs, electricity is increasingly in demand. And regardless of how it is produced, one thing is for sure: it needs a grid to get to us. Power transmission and distribution systems have undergone little or no change in the past, but with the large-scale integration of renewable energy into the grid and more decentralized generation, that paradigm is about to be turned on its head.

Power grids were born out of the need to bring together those who generate and those who consume electricity. Historically, it was generated in large power plants, which were usually located in isolated areas, spewed out a lot of smoke, and gave off an unpleasant smell. Then, this mass-produced electricity had to be delivered, especially to cities, where demand was most concentrated.

The energy transition is changing this paradigm. Today, there are almost no thermal power plants left. Electricity is generated in a fully distributed way, wherever there is space to set up wind turbines and solar panels. The number of producers has grown significantly, and new ways of producing lower amounts of power, in the context of cogeneration or generation from renewable sources, have emerged.

“The grid has to be very flexible and it has to have tools that allow it to be flexible. Batteries enable it to be just that.”

But if these technologies require less space, the connection of these various distributed generators ends up having to be located where the grid is closest. And that was not something that was considered from the beginning, because the Portuguese and Spanish ultra high voltage transmission grid operators (REN and REE, respectively), had no way of knowing how things would evolve when they set up the system.

To use an analogy, the transmission grid works like a kind of electricity highway, which is connected to all kinds of roads and even dirt tracks. E-REDES is the company that manages the flow of the distribution grid through all those back roads, and the challenge now is to have the capacity to accommodate all the electricity coming from the new sites using systems that, in most cases, are not ready for it.

Pedro Godinho Matos, head of business development at E-REDES, says that “if we have a lot of generation coming from a place where the grid has limited capacity, there are going to be constraints.” To use the traffic metaphor again, those back roads do not have the same capacity to carry electricity and there is no easy way of controlling how many vehicles are traveling on those dirt tracks.

“There are two ways to solve grid congestion: build more grid; or be more flexible, find ways to ensure that those who want to travel along the road can do so at a time that is more useful from the point of view of the grid managers,” he explains. “If everyone wants to go from Lisbon to the Algarve at the same time, we know that the road is going to get jammed. The solution is either to build a new road just for those occasions, which isn’t very efficient because most of the time it will be empty; or you can hire flexibility and, in that case, the example is to pay someone to stop for a coffee, or to stay at home and not go until the next day.”

In the case of electricity, the solution could be to give incentives to those who want to use the grid in order to adapt their behavior and make sure the grid is able to respond as effectively as possible to the incentive. In other words, it is not about not using or cutting back on energy consumption, but rather consuming it at times when the grid infrastructure - which is paid for by everyone - can handle everything that is needed, avoiding those peaks in demand.

“The aim of E-REDES is not to stop anyone, but for the traffic to flow,” says Pedro Godinho Matos. “All requests are accepted. We just need to hire someone to help organize that ‘electricity traffic’.”

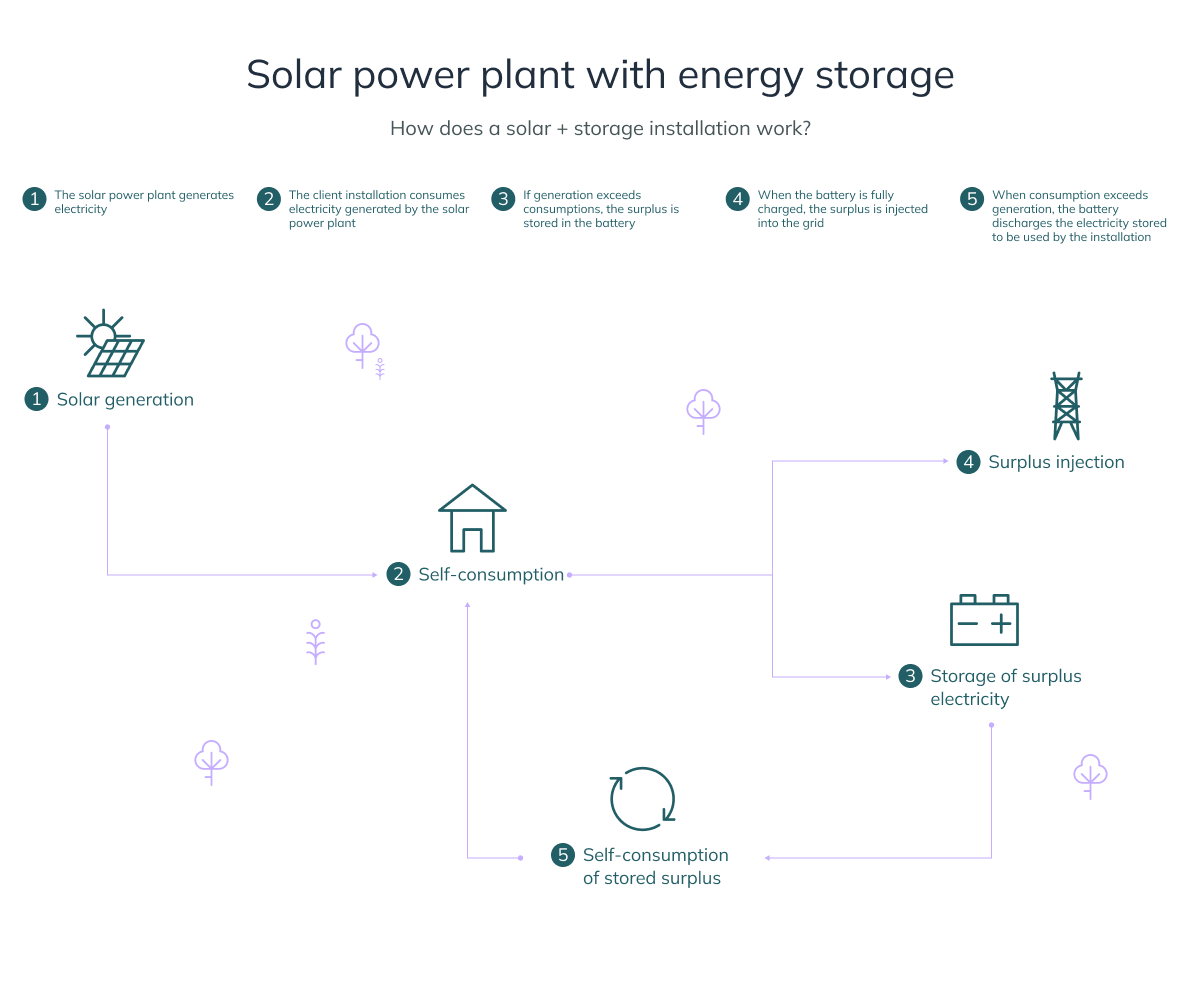

In the specific case of solar power, at peak sun, there are a number of power plants generating a substantial amount of electricity. The substations, however, do not have the capacity to absorb all that energy. So, either you build twice as many substations (which is unthinkable, given the cost) or you find a way to store energy at peak times, so that it can flow through the existing infrastructure later on.

“It’s much more efficient to maximize the use of what we already have, because the infrastructure is already in place, with no additional costs,” he explains. “The grid has to be very flexible and it has to have tools that allow it to be flexible. Batteries enable it to be just that. The issue is that, for now, storage is still expensive. Who wants to spend millions to store only a few euros worth of energy?”

The reality is that, following a decade during which generation from renewable energy sources has not increased by more than around 10% a year, the figures in the revised Portuguese National Energy and Climate Plan for 2030 suggest that the amount of energy flowing through the grid could potentially double. It is a tremendous growth that represents a major challenge for everyone involved. All of this electricity must be absorbed. And that means more grids and more flexibility to reach every corner. With no New Year’s Eve blackouts.